Logistical masterstroke: 75 year anniversary of the Berlin Airlift

How do you supply a city of millions from the air alone?

- Airfreight Insights

- Facts

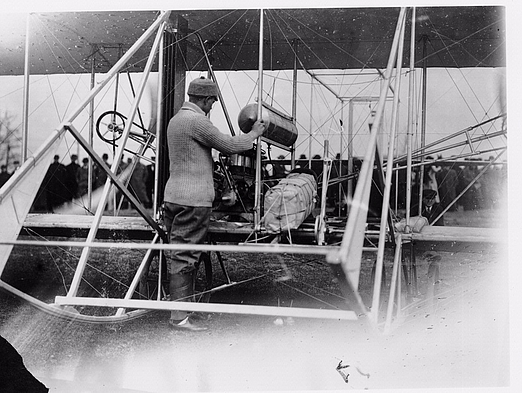

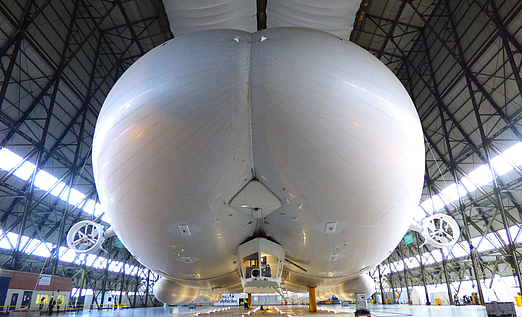

Seventy-five years ago, the Soviet Union imposed the Berlin Blockade, and in an instant, millions of Berlin residents were cut off from the rest of the world. Under the leadership of the Western powers, it was quickly decided to supply the metropolis from the air. This marked the start of a logistical masterstroke that defied belief. The residents were supplied not only with food and medicine but also with tons of heating fuel over the winter. Learn more about the so-called “air bridge,” 1,398 flights in 24 hours, “raisin bombers”, camels and seaplanes filled with salt that landed on Berlin’s lakes.